Moon Monday #87: A Schrödinger cat-like CLPS program, Artemis I launch-bait, and more updates

This week’s Moon Monday is a CLPS special, with all of its promises, risks, and drama. I hope you enjoy the deep dive as much as I did writing it. :)

NASA eyes prestigious farside Moon landing in boldest CLPS bet yet

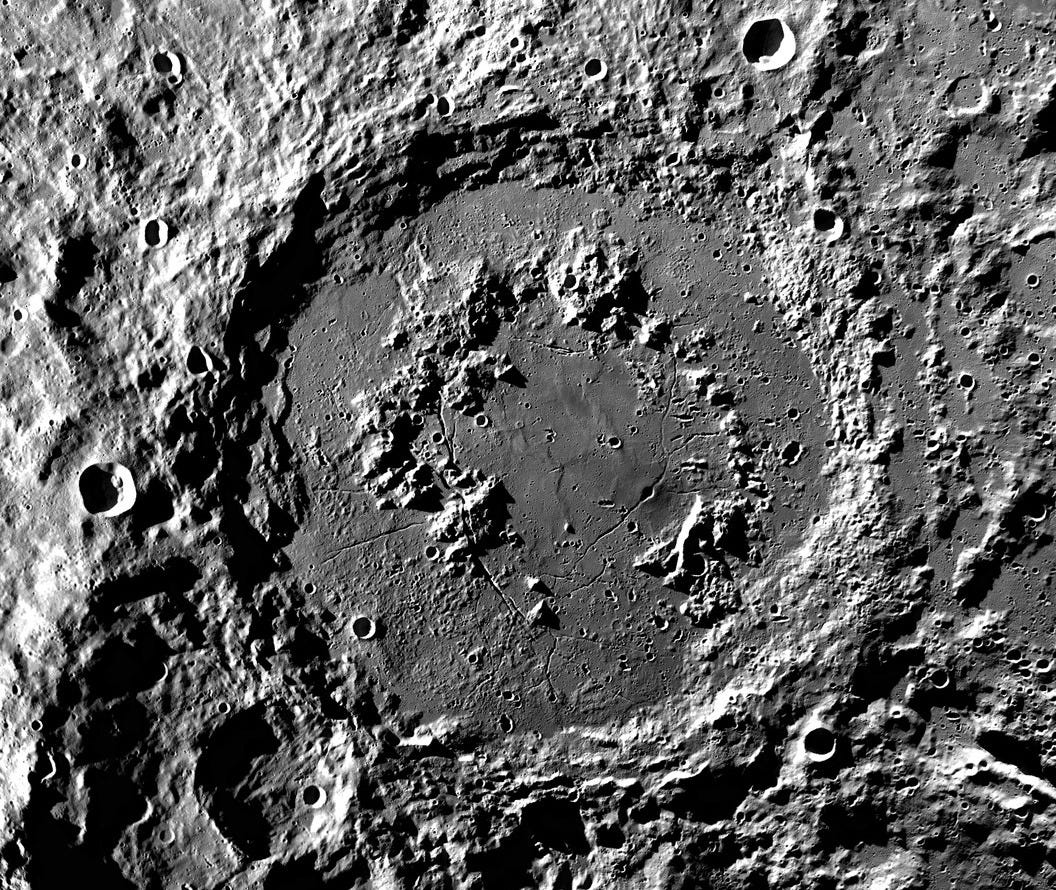

Last week NASA awarded its eighth contract under the CLPS program to send the agency’s instruments and payloads on commercial landers to the Moon. Draper, the winning company, is tasked with landing a spacecraft on the lunar farside, a feat only achieved by China’s Chang’e 4 mission so far. The landing region chosen by NASA for the 2025 mission is no less impressive—the 312 kilometers wide Schrödinger crater, a pristine destination long asked for by the global scientific community.

Since the Moon’s farside isn’t visible from Earth, Draper’s lander will deploy two Blue Canyon-built satellites in cislunar orbit similar to Chang’e 4’s Queqiao spacecraft to relay communications between the lander and Earth. The lander will carry 95 kilograms of NASA’s scientific instruments, which should yield more science compared to prior CLPS selections on average thanks to the agency’s young PRISM initiative. The mission will deploy two distinct, lunar-night-surviving seismometers, the most sensitive ones ever sent to space. Over at least four months of their operation, they will help us better understand the Moon’s internal structure and how it evolved, and know the amount and rate of micrometeorite impacts on the farside to help plan future crewed Artemis missions.

The lander will also carry a drill, a probe, and a magnetic sounder to measure the farside crust’s internal heat flow and electrical conductivity in a way that will resolve murkiness of its thermal and compositional structure. There’s also a non-PRISM experiment to study electric and magnetic properties in the region, which shielded from Earth’s electromagnetic interference is apt for studying the solar wind’s interactions with the surface, and for characterizing the Moon’s radio emissions for future farside radio telescopes.

This is perhaps the boldest CLPS mission yet, or at least one promising the most bang for the buck. Draper bid only $73 million for NASA’s task order request, making it the second lowest CLPS contract thus far (the cheapest is Intuitive Machines’ second Moon landing at $47 million). And what NASA could get for that $73 million, roughly 10 times less than the agency’s Discovery class missions, is a prestigious farside landing in a geologically pristine treasure-melt pond.

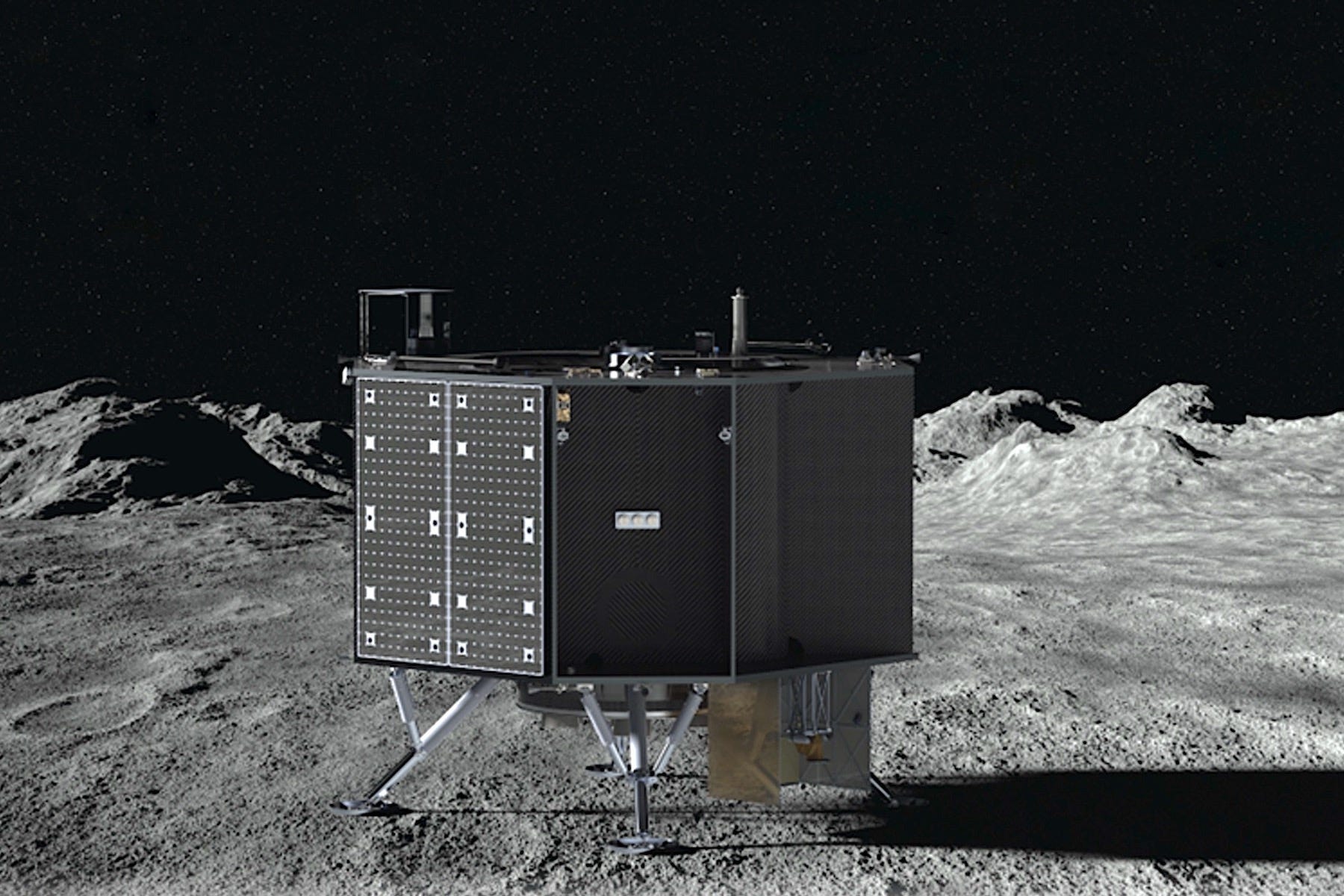

Curiously, something neither NASA nor Draper have mentioned in their respective press releases is if the lander will also carry UK’s Lunar Pathfinder orbiter. As part of a NASA-ESA June 2022 agreement, Pathfinder is supposed to launch on a CLPS lander by 2025, in return for which NASA can use the orbiter for communicating with its farside and polar hardware, presumably including Draper’s mission. The next two CLPS selections are launching in 2026 so they’re unlikely to carry Pathfinder. As the only 2025 CLPS launch, Draper’s lander seems to be the most likely to onboard the orbiter. Also, the 280-kilogram Pathfinder is too heavy for most CLPS landers. Since Draper’s lander is directly based on ispace’s vastly more capable Series 2 lunar lander design compared to Series 1, it can deploy up to 500 kilograms of payload to the surface or up to 2,000 kilograms in lunar orbit. Depending on the mass of the two Blue Canyon communications satellites, Lunar Pathfinder could be within the Draper lander’s deployment reach.

Update on August 1, 2022: Regarding the lack of clarity on Lunar Pathfinder’s launch, a CLPS vendor source tells me that NASA will soon release a dedicated competitive bid for it.

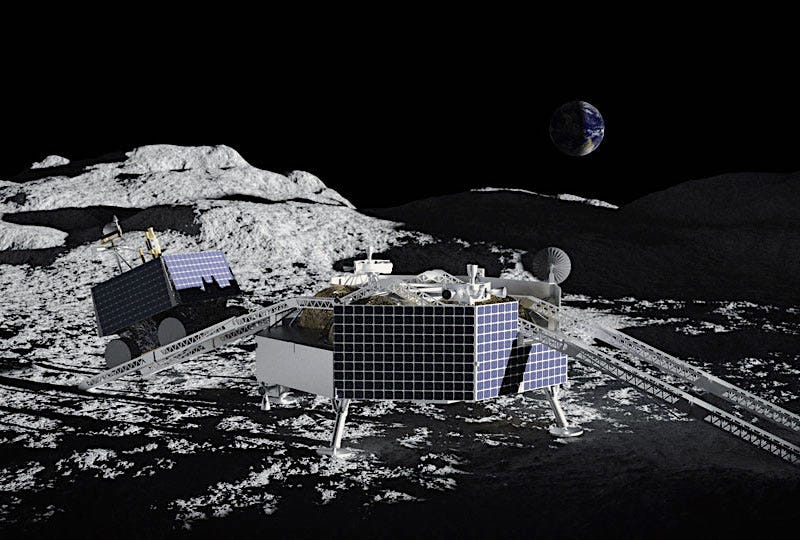

NASA borders on traditional, cautious approach with the VIPER mission

If the farside mission is CLPS’ latest program-pushing bet, NASA’s VIPER rover is where the trait began. But since the mission is paramount to understanding the nature of the Moon’s polar water ice and for planning near-term crewed missions, NASA is taking a more conservative approach with VIPER than other contracts. Recently NASA requested Astrobotic to delay VIPER’s delivery to the Moon’s south pole from November 2023 to November 2024. NASA is paying Astrobotic an additional $67.8 million to do additional testing of their large, 5900-kilogram Griffin lander to reduce mission risk. Astrobotic’s VIPER contract now stands at $320.4 million, making it the most expensive CLPS mission.

Concerns about VIPER aren’t new. For one, the April 2022 report from NASA’s Office of Inspector General pointed out that the agency doesn’t have a reliable true cost estimate for the mission because unlike traditional ones, NASA is separating its own costs to build and operate VIPER (currently at $433.5 million) from the funding it’s providing to Astrobotic (originally $199.5 million). The second concern, as reported by Eric Berger, was that owing to VIPER’s vitality, NASA had briefly considered a traditional delivery for the rover. But the higher costs and timelines for bypassing CLPS for VIPER would’ve effectively killed the program, which NASA’s Science Mission Directorate (SMD) as CLPS’ managing body wouldn’t accept. Ultimately, NASA asked Astrobotic to better test Griffin’s propulsion system and reduce risks while the agency nevertheless began building a backup instruments set.

Many thanks to Epsilon3 for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday.

Masten’s CLPS Moon landing mission in free fall

According to a July 14 report by Douglas Messier, Masten Space has furloughed its employees and recently laid off many who were exclusively working on its first Moon landing mission part of NASA’s CLPS program. It would seem that Masten underbid by $30 million to NASA for its eventually awarded contract of $75.9 million, with said remainder amount failing to come from a private customer who intended to fly payloads onboard. In a response to Messier, NASA said it’s working with Masten to figure out the exact impact of the situation, and that if Masten is unable to deliver the agency’s payloads, they’ll be relocated on other CLPS flights.

This is really sad, not just for what seems to be the end of Masten’s CLPS Moon landing but also the trove of other promising, previously-funded lunar or related technologies Masten was developing, including a mobile rocket miner, a lunar night survival system, the suborbital Xogdor for reduced gravity testing and validating lunar navigation and landing technologies, near-instantaneous landing pads to be made by future landers, and more.

How do CLPS selections work?

Considering that all of today’s highlight stories are about CLPS, with takeaways from each revolving around pricing for varied reasons, it’s worth at least briefly discussing how CLPS mission selections work. When NASA started CLPS in 2018, it invited all interested U.S. companies to present their robotic lunar landing capabilities. After evaluating proposals chiefly on the basis of technical merit and feasibility, NASA selected a total of fourteen companies—nine in 2018 and another five a year later—who can bid on each CLPS lunar landing task order from NASA until 2028.

NASA decides the landing site and delivery year for each task order, and what scientific instruments it prefers onboard. It then puts out these requirements for the CLPS vendors to bid on. Based on how well each bid fairs in terms of technical merit, pricing as well as schedule, NASA awards a CLPS task order to a company.

For NASA, each order delivers the community’s scientific instruments at a far lower cost than a dedicated, traditional mission while covering end-to-end services. The selected company is responsible for integrating NASA’s payloads onto their craft, landing on the Moon, operating the lander, and sourcing their own mission infrastructure, including booking a rocket to fly on and availing ground station services for the lander to communicate with Earth.

With a roughly order of magnitude lower price for NASA, the agency is willing to accept a 50-50 chance of success with CLPS missions, especially considering that only three countries have landed anything on the Moon so far. Even if only half the CLPS craft nail the landing, the entire program’s cost of $2.6 billion over 10 years amounts to way less than the $4.1 billion of one Artemis SLS+Orion launch, or rather costs about the same as just three Discovery missions to make a more relevant comparison. SMD deems the return to still be plentiful. If missions like the farside Draper landing deliver, it’s a boon. But for cases like Masten, it’s a lesson in how CLPS’ structure encourages undercutting, which risk not just the missions but entire companies.

CLPS seems to be like Schrödinger’s cat; we will just have to witness the program unfold to find out how valuable it turns out to be, and if and how it (hopefully) evolves.

More Moon

- NASA is targeting August 29 as the earliest possible launch of the Artemis I mission to send an uncrewed Orion spacecraft around the Moon and back, with the next opportunities being on September 2 and 5 respectively, all assuming a decision to roll the fully stacked SLS rocket to the launchpad on August 18. As part of launch preparations, technicians installed the suited manikin Campos inside Orion last week. Sensors on its seat will record acceleration and vibration throughout the mission. Five additional accelerometers inside Orion will complement that data, including during the final mission phase of bounced atmospheric reentry and splashdown. NASA has a regularly updated page for Artemis I launch windows throughout this year.

- TASS reports that Russia’s Luna 25 Moon landing mission will most likely launch no earlier than 2023 because of inadequately functioning landing sensors in recent tests.

- NASA and Northrop Grumman successfully test fired the SLS rocket’s upcoming new booster design I covered last week. NASASpaceflight has interesting technical details on its design.

→ Browse the Blog | About | Donate ♡