Moon Monday #126: China’s next two lunar missions, India’s ambition to mine Luna, and more

China to launch Queqiao 2 and Chang’e 6 lunar missions next year

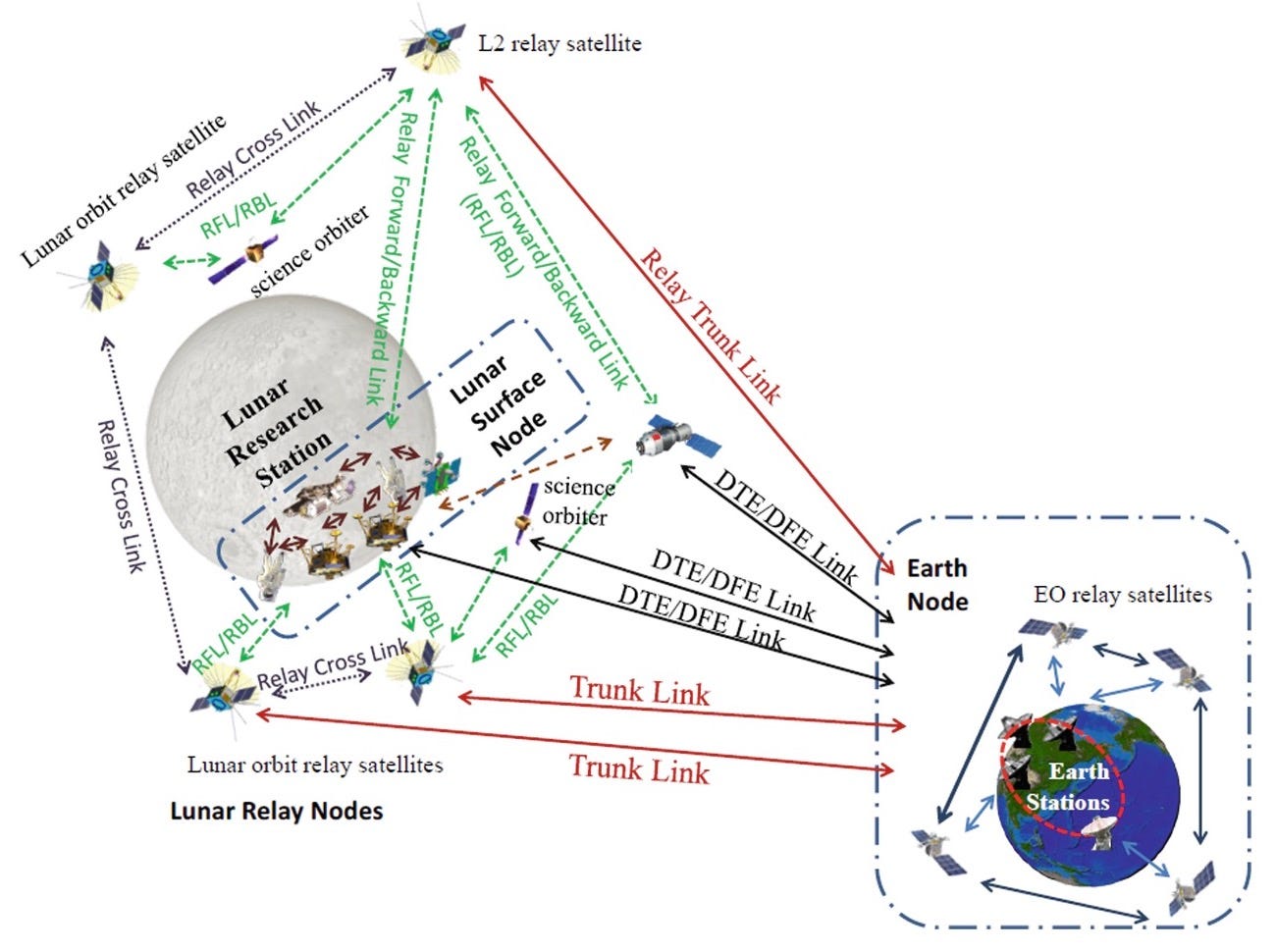

Queqiao 2 relay satellite

China is on track to launch the Queqiao 2 lunar orbiter by May next year, Andrew Jones reports. Its 4.2-meter wide parabolic antenna will relay communications between Earth and CNSA’s upcoming Chang’e 6, 7, and 8 Moon landers. Unlike the first Queqiao relay satellite, which is halo-orbiting the Earth-Moon Lagrangian point #2 for the farside Chang’e 4 mission, Queqiao 2 will be in a Distant Retrograde Orbit. Said orbit is exactly what the still-active “service module” of China’s Chang’e 5 mission has been testing since December last year.

In fact, Queqiao 2 will be part of a larger satellite constellation providing navigation and communications (navcom) for hardware as well as crewed missions on and around the Moon as part the upcoming Sino-Russian long-term scientific Moonbase called the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS). Chang’e 7 and 8 will represent a formal beginning of the ILRS project. One of these two spacecraft is expected to deploy another navcom orbiter to join Queqiao 2.

ESA’s Moonlight initiative also aims to provide a navcom lunar service, and will set in motion with the launch of UK’s Lunar Pathfinder orbiter in 2026. Lockheed Martin’s newly formed subsidiary Crescent Space is targeting launch of the first two satellites of its envisioned lunar navcom constellation Parsec in 2025. More vying competitors in this space include ArkEdge Space, Aquarian Space, and Plus Ultra.

Chang’e 6 sample return

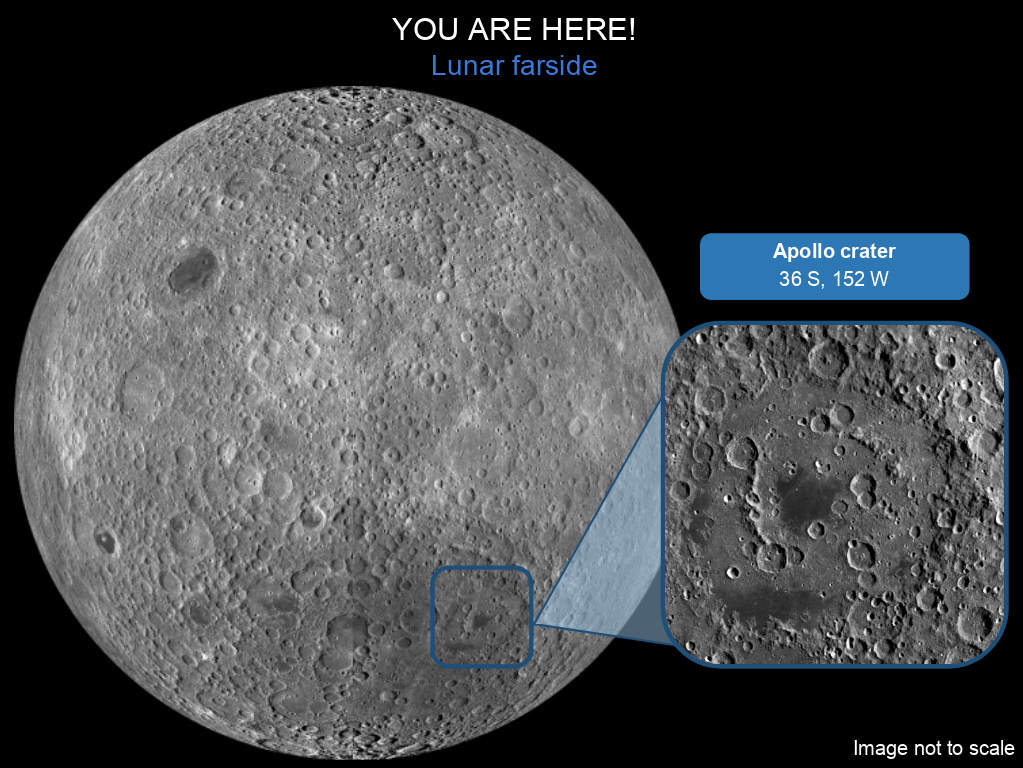

China’s Chang’e 6 mission aims to bring about two kilograms of lunar samples to Earth, with a similar mechanism and mission profile to Chang’e 5 but with an improved sampler. The Chang’e 6 samples will be scientifically even more valuable since the mission’s landing site lies within the 3.9-billion-year old Apollo impact crater on the Moon’s farside.

The Apollo crater lies within the largest and deepest crater on the Moon, the South Pole-Aitken (SPA) basin. Since this ancient crater holds clues to what was happening in our early Solar System about 4 billion years ago, a sample return mission from here has been assessed as a top priority in the latest Planetary Decadal Survey—a report produced every 10 years by the US scientific community to guide future NASA missions. Furthermore, the SPA-creating impact excavated deep into the Moon’s crust and mantle. Since the Apollo crater formed later, its impact might have uplifted deeper crustal materials, ready to offer insights into our Moon’s interior and evolution. It’s to this end that NASA had chosen the Apollo crater as a candidate Constellation Landing Region.

At 500 kilometers wide, Apollo is a huge crater and there are tradeoffs to be made between the scientific richness and engineering plausibility of landing sites within. Let’s hope that the Chang’e 6 lunar samples would nevertheless contain at least traces of ancient lunar material key to understanding our Moon’s evolution and origin.

The Chang’e 6 lander will also carry three European scientific instruments:

- CNES’s DORN instrument will measure the noble gas radon leaking out of the Moon’s surface, which would be evidence that our Moon and Earth do indeed share an origin. It will also study volatile gases such as water vapor in the Moon’s exosphere.

- Italy-based SCF Lab’s INRRI retroreflector, which will reflect laser beams sent from Earth to make precise distance measurements, and from it infer properties of the lunar core and the Moon’s drift rate away from Earth.

- NILS, an instrument from the Swedish Institute for Space Physics, will detect highly energetic neutral solar wind atoms which slam and get reflected from the Moon’s surface. This will help scientists study surface elements as well as local magnetic fields.

The Chang’e 6 orbiter will carry a Pakistani CubeSat called ICUBE-Q, which would make it the country’s first Moon mission.

India wants to mine the Moon too

India’s new space policy, approved by its government in April, states for the first time the country’s novel ambition to extract and use space resources. While the document’s chief purpose is to clarify the nature and extent of space activities Indian private businesses are now being encouraged to pursue to grow the nation’s space economy, it is the two mentions related to space resources that are pertinent to our Moon.

Non-Governmental Entities shall engage in the commercial recovery of an asteroid resource or a space resource. Any NGE engaged in such process shall be entitled to possess, own, transport, use, and sell any such asteroid resource or space resource obtained in accordance with applicable law, including the international obligations of India.

In fact, ISRO is being encouraged to specifically carry out missions to said end.

ISRO shall undertake studies and missions on in-situ resource utilization, celestial prospecting and other aspects of extra-terrestrial habitability.

The phrasing “commercial recovery of an asteroid resource or a space resource” is interesting because it includes the Moon without mentioning it. You see, India is a signatory of the 1979 Moon Treaty, which has strict and even highly idealistic non-sovereignty underpinnings. Being seen at odds with the Moon Treaty with such a policy direction could become an overnight concern with one misstep.

None of the indigenously crewed spacefaring nations of the US, China, and Russia have signed the Moon Treaty, and don’t plan to. The US-led Artemis Accords also controversially intends to set precedence for local resource extraction on the Moon. There is international concern that the Accords ultimately might—but doesn’t yet—put its signatories in objection of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which India has also signed. The US and three other signees of the Accords—Japan, Luxembourg, and UAE—have passed national bills to allow their private companies to extract space resources and use or sell them.

While India’s space policy is yet to morph into a bill, there’s little doubt that India taking a stance similar to the Accords doesn’t gel along with its commitment to The Moon Treaty. And so, will India withdraw from The Moon Treaty just like Saudi Arabia did? Between the new policy and growing Indian-US space relations, the chances of India signing the Artemis Accords are certainly higher now.

Many thanks to Epsilon3 and The Orbital Index for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday.

Testing for the Moon on Earth

- China is building new space-simulating facilities dedicated to Moon exploration in preparation for upcoming crewed missions, CCTV says. One such facility where trial operations are ongoing is a comprehensive lunar dust simulator, which can impart electric charges to simulated lunar soil, and even loft dust particles with vibrators. Relatedly, Andrew Jones recently reported about China’s staged descent lander concept for landing astronauts on the Moon before 2030.

- The Luxembourg-ESA co-run European Space Resources Innovation Centre (ESRIC) is establishing a terrestrial pilot plant to accelerate as well as de-risk technologies and concepts related to extraction and utilization of lunar resources before their use in actual Moon missions.

More Moon

- On May 3, the Czech Republic became the 24th country and seventh ESA member to sign the US-led Artemis Accords. The country is contributing sensors as part of ESA’s deep space radiation experiments ERSA and IDA onboard the upcoming NASA-led international Gateway lunar orbital habitat. With the signing of the Accords, Czech Republic and the US both expect academic and industrial space ties to develop and strengthen.

- Israel-based Lulav Space—who aided the world’s first private lunar orbiter Beresheet with guidance, navigation and control (GNC) technologies—is partnering with Sidus Space to offer modular GNC products and services to US companies building Moon missions. Aside: Lulav is continuing to provide GNC for the twin Beresheet 2 landers, which are targeting a 2025 launch. Sidus provides some hardware components and testing support for NASA’s SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft for Artemis Moon missions. Notably, Sidus has also partnered with KSAT, which offers dedicated lunar ground stations to meet communications needs of the increasing number of (commercial) Moon missions.

- As part of the 2023 NASA Entrepreneurs Challenge, the agency is encouraging public proposals for lightweight science & technology payloads that might be co-funded for a future commercial flight to the Moon as part of NASA’s CLPS program. The proposals should align with NASA’s Moon to Mars Objectives or the Decadal’s lunar recommendations.