KPLO, South Korea’s first Moon mission

The lunar orbiter launched South Korea’s deep space ambitions.

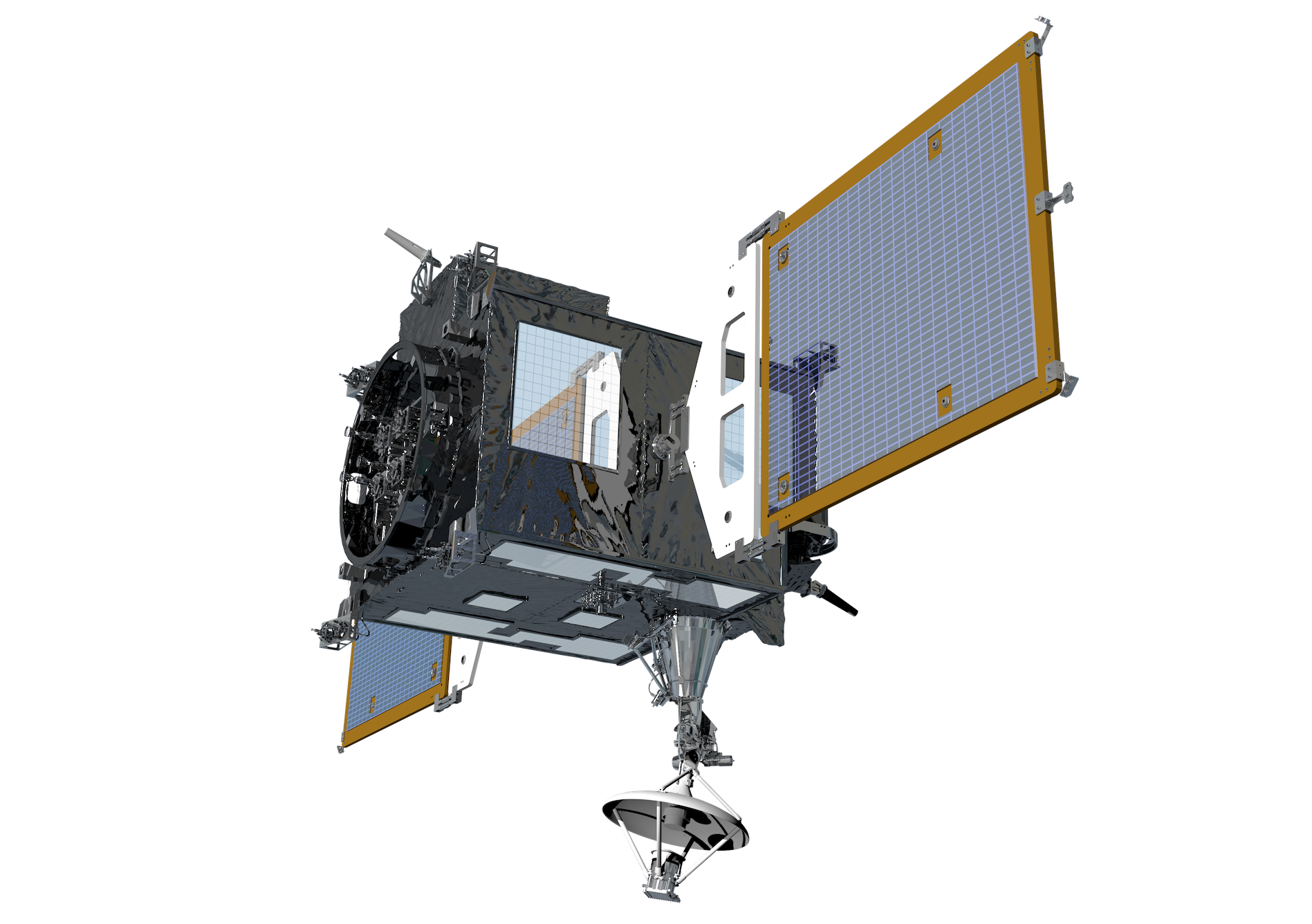

On August 5, 2022 (KST), a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket launched the Korea Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter, or KPLO, to the Moon. On December 17, KPLO successfully entered lunar orbit, making it South Korea’s first such spacecraft. With KPLO, South Korea has forayed into planetary exploration, begun its lunar exploration program, and found a collaborator in NASA. Equipped with 4 indigenously built instruments and a NASA-provided camera, KPLO will show us new views of the Moon’s surface and help us plan future missions there, including landing humans on its poles.

How will KPLO study the Moon?

KPLO was launched on a ballistic lunar trajectory, which allowed it to reach the Moon in a fuel-efficient manner over four months. After entering a roughly 100-kilometer circular lunar orbit, KPLO will study the Moon for at least a year with its 5 scientific instruments starting in January 2023.

KPLO sports two indigenously built cameras, one of which will image the Moon’s surface at a high resolution of 2.5 meters per pixel. The other is a wide-angle polarimetric camera which can determine the type of surface materials based on the way light reflects and scatters off them. This will help us better understand the Moon’s surface composition and the nature of its varied volcanic deposits.

KPLO also has a gamma-ray spectrometer, which will look at highly energetic gamma rays released from the Moon. The energy levels of these rays are linked to the elements that produce them, allowing scientists to determine the elemental makeup of specific Moon materials. Together with the polarimetric camera, KPLO will better help understand the Moon’s mineral composition, and how its terrain has evolved over four billion years.

The last of KPLO’s indigenous instruments is a magnetometer. While the Moon has lost its global magnetic field, it does have localized magnetic features such as “swirls.” By measuring their weak magnetic fields from orbit, KPLO will help us understand the extent of protection they offer from harmful space radiation, and the nature of the Moon’s leftover magnetic areas as hints of its past.

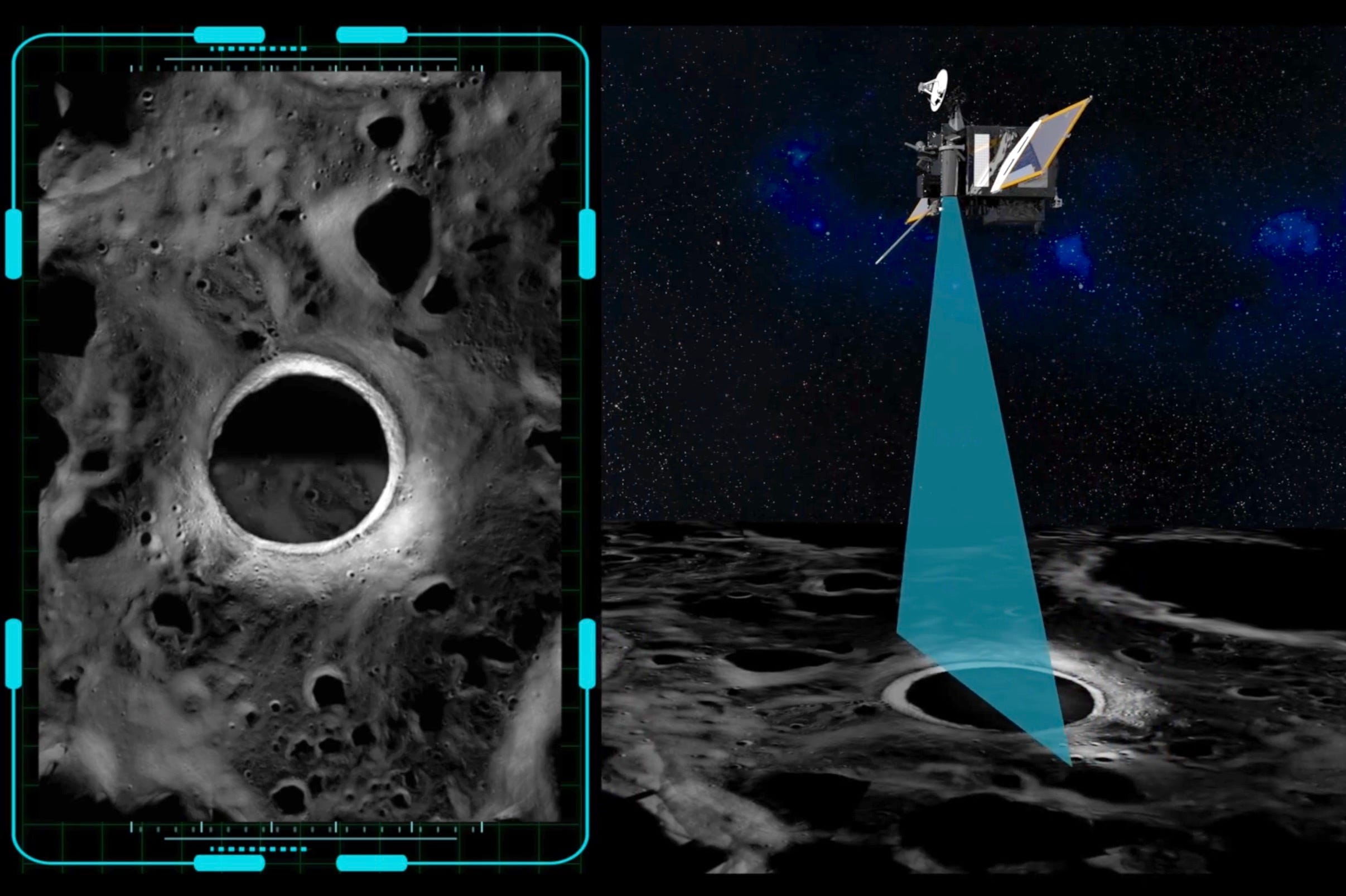

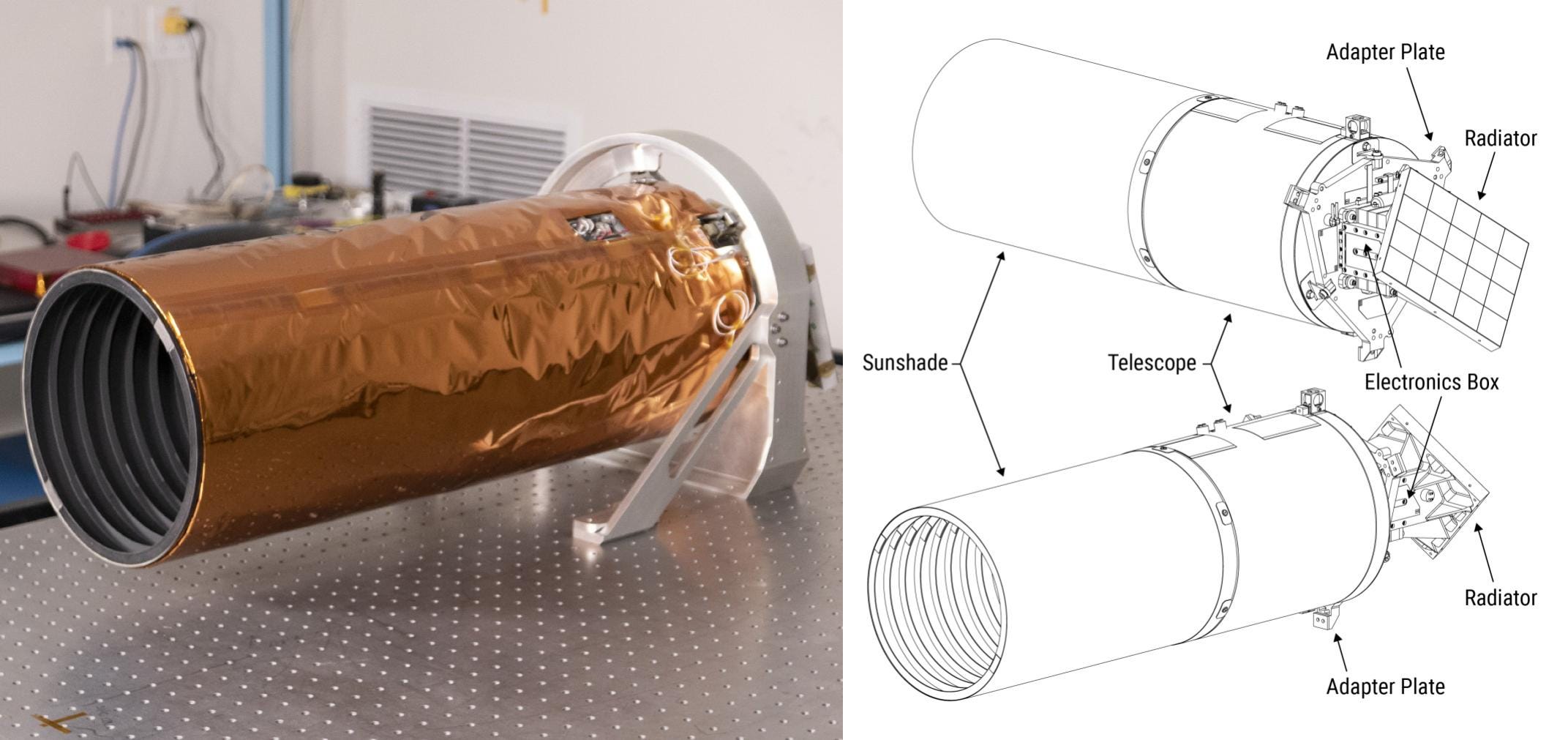

KPLO’s final instrument, ShadowCam, is an ultra-sensitive camera provided by NASA to see inside permanently shadowed regions on the Moon. It will provide critical information about the terrain and water in such regions to help plan future crewed and robotic missions there.

How will ShadowCam see inside permanently shadowed regions?

On the Moon’s poles, the Sun sits very close to the horizon, so even small features like rocks cast very long shadows. Likewise, large craters with terraced edges block sunlight from entering the craters. Scientists call such places “permanently shadowed regions” because they’re eternally dark. They are thought to host water ice and other resources that are central to future lunar exploration plans by space entities worldwide.

While sunlight doesn’t reach and thus directly reflect from the Moon’s permanently shadowed regions, a minute amount of sunlight does scatter into them from nearby terrain. This light reflected back into space is incredibly dim but detectable by current orbiters such as NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and ISRO’s Chandrayaan 2 orbiter. However, their cameras aren’t sensitive enough to peer into the darkness and help meticulously plan landing and roving missions in and around such regions. That’s where ShadowCam comes in.

ShadowCam’s camera is at least 200 times more sensitive than the one on the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. This will allow it to see a shadowed region on the Moon as if it was sunlit! ShadowCam will map the terrain inside permanently shadowed regions with a very high resolution of up to 1.7 meters per pixel, and help locate their water ice deposits and other such volatile resources based on how they reflect light. This will tell us how abundant and accessible these resources are—a crucial step towards safely and affordably planning future missions to the lunar poles and building sustainable habitats.

How are NASA and South Korea collaborating to explore the Moon?

ShadowCam isn’t the only NASA contribution to KPLO. In March 2021, NASA selected nine scientists to join KPLO’s science team to help enhance the mission’s scientific output. NASA is also providing technical assistance on mission design, deep space communications, and navigation technologies.

In November 2022, KPLO successfully demonstrated a kind of space internet that’s resistant to disruptions in communications. KPLO sent media files, including popular South Korean band BTS’ music video, from more than 1.2 million kilometers away.

On May 24, South Korea signed the Artemis Accords, which NASA calls “a practical set of principles to guide cooperation among nations participating in NASA’s 21st century lunar exploration plans.” This means scientific data can be easily shared between the two countries, and that there will be several opportunities for both countries to continue cooperating on future missions.

What’s next for South Korea in lunar exploration?

The $182 million KPLO mission comprises the first phase of South Korea’s lunar exploration program. In the second phase, the country plans to launch a fully indigenous Moon landing mission in 2032.

Special thanks to Eunhyeuk Kim of KARI and Mark Robinson of Arizona State University for reviewing the initial version of this article.

Originally published at The Planetary Society.

I also wrote a follow-up post on how this mission will inspire kids and students in South Korea, and how India's Chandrayaan 1 did the same for me.

Following a public contest, the South Korean space agency has nicknamed the mission as Danuri, a blend of the Korean words “Moon” and “enjoy”.

→ Browse the Blog | About | Donate ♡